Dawn of "Total War" and the Surveillance State

— Allen Ruff

[Slightly edited and with illustrations and URLs added, the following originally appeared in Against the Current #190, Sept.-Oct., 2017 as part of my ongoing series marking the centenary of World War I. -AR]

UNITED STATES ENTRY in World War I a hundred years ago set in motion a series of domestic transformations that continue to reverberate. In its efforts to mobilize society for “total war,” a still nascent corporate liberal state expanded its scope and authority and in doing so laid foundations and set precedents for the expansion of executive power and the rise of the national surveillance state.

That “war at home” was waged on numerous fronts as a federally coordinated ideological campaign shaped a hyper-nationalist climate of anti-foreign and anti-radical intolerance, coercion, extralegal violence and state repression that hammered all dissent. A brief survey of that early war period tells us much about how ugly, indeed dangerous, it can become for those deemed “disloyal,” “subversive,” “illegal” or “alien” in times of “national emergency” when conformity becomes a test of loyalty.

The “European War” had already been underway since August, 1914 when president Woodrow Wilson asked Congress for a formal declaration of war against Germany on April 2, 1917. (See: Ruff, on US Entry in World War I...) With that turn to war, the country’s ruling circles faced an immense set of challenges. They not only had to mobilize war production and allocate, raise and provision what became a four million-strong military force, but had to overcome widespread popular opposition and reluctance to join in the murderous, far-off bloodletting.

U.S. entry came on the heels of over a half century of recurring social upheaval and class conflict, the result of unregulated capitalist expansion, unbridled competition and the concentration of economic and political power. As the country went to war, immigrants and the children of immigrants comprised a third of the population.

Approximately twelve million newcomers had arrived during the latter 19th century, another eighteen million came prior to 1914 and those of German heritage made up the country’s largest single ethnic group. Millions of those “new immigrants” provided the labor at the base of the industrial economy but with the war, large numbers of them, hailing from the German and polyglot Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, the “Central Powers,” remained far from eager to take up arms against their homelands.

Additionally, with Tsarist Russia still part of the “Triple Entente” until after the 1917 "October Revolution," masses of Poles, Finns, Balts and Eastern European Jews also remained unsympathetic to the Allied cause. A sizable portion of the Irish American population, with the Dublin “Easter Rising” of 1916 and execution of its leaders fresh in its memory, also felt, at best, marked ambivalence regarding any support for the British. Besides, a great many of these pre-war numbers had immigrated not just for work and opportunity but to avoid military conscription.

Such were the social divides — not just of class, but race, ethnicity, gender and regional differences — that in his 1916 reelection campaign Wilson simultaneously campaigned on the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War” while promoting war “preparedness.”

A Southern-bred Democrat steeped in a white supremacist world view of American mission and racist notions of a civilizational hierarchy of peoples, he also played to deep-seated “old stock” anti-immigrant bigotry. Wilson repeated nativist calls for “100% Americanism” — the programmatic assimilation of “hyphenated-Americans,” those Southern and Eastern Europeans widely viewed as “inferior stock.” They were seen as the cause of the era’s social ills, labor strife and purveyors of “European radicalism.”

The war abroad intensified social tensions. Beginning in early 1915, some $2 billion in Entente orders for war-related commodities set off a boom, an expansion of investment, productive capacity and output and a related demand for labor. (The original triple Entente powers were France, the British Empire and the Russian Empire.)

That demand, already heightened by the war’s disruption of an annual cross-Atlantic flow of some 250,000 migrant workers, provided new leverage for the exclusivist skilled craft union affiliates of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), the railroad brotherhoods and the industrially organized United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), as well as those unorganized mobile workers able to sell their labor to the highest bidder.

It also presented new opportunities for the revolutionary unionists in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), veterans of more than a decade of struggles to organize the supposedly “unorganizable” among the largely immigrant “unskilled” of the industrial Northeast and Midwest and masses of itinerant workers engaged in timber, metal mining and agriculture across the Upper Plains and far West.

Northern labor demand also helped stimulate the first African-American “Great Migration” from the rural South, central to an understanding of the period. (See: Ruff, "A World Made More Unsafe: African Americans & World War I...")

Accelerating after U.S. entry, that war-induced boom not only brought immense corporate profits, but also fueled an inflationary spiral in the cost of living as prices for basic necessities outstripped wage increases. (Between 1913 and August, 1917 wholesale food prices rose 80% while the average retail price increased by 49%).

Living and working conditions declined as employers, encouraged by the initially relaxed enforcement of existing federal and state labor laws, eroded or ignored already minimal standards and protections. Varied and combined grievances — speedups, longer work weeks, deskilling of trades through mechanization, the introduction of “scientific management,” a lack of grievance procedures and union recognition, the “open shop” and increasingly perilous work conditions — provoked increases in union membership and a major upsurge in strike activity.

The period between April and early October 1917 witnessed some 3,000 documented walkouts by unionized and non-union workers in numerous industries, several of which involved upwards of 10,000 strikers and took on the character of city- or region-wide general strikes. That upsurge triggered a rapid response from a Washington establishment determined to prosecute the war, and by those corporate leaders eager to assure “industrial peace” and unprecedented profits.

With U.S. entry came a torrent of Executive Orders and Federal legislation that led, by early 1918, to the expansion or creation of some 5,000 wartime agencies, regulatory committees, oversight boards and federally-run corporations routinely headed by business elites dedicated to boosting and coordinating the war effort.

As a result, those elite “dollar-a-year men” succeeded in derailing those limited prewar Progressive Era regulatory initiatives curbing monopolies and the power of financial and industrial capital. As a result, the corporations dictated the terms of wartime mobilization as the war propelled the integration of the modern corporate liberal state.

In his April, 1917 Congressional message, in which he defined the U.S. war aim as the liberal interventionist mission to make the world “safe for democracy,” he vowed that any “disloyalty” would meet with “a firm hand of stern repression.” That June, he charged that “German masters” were using socialists and the “leaders of labor” and “employing liberals in their enterprise” to “undermine the Government.”

The day war was declared and with anti-German hysteria already at a feverish pitch, Wilson resurrected the Alien Enemies Act, part of the “Alien and Sedition Acts” of 1798, to order the registration of all adult male German nationals. Broadened that fall, the measure barred all “enemy aliens” 14 years and older from places of “military importance” including Washington, D.C. and required them to seek permission to travel within the country or change residence.

The order was extended to include women the following April. Under its authority by war’s end, some 600,000 German citizens, regardless of their length of stay in the country or beliefs, would come to report to local post offices and police stations where they were fingerprinted, photographed, filled out forms and swore a loyalty oath. Denied due process and held under Justice Department administrative authority, some 6,300 of them were detained as a “deterrent” and 2,300 were confined to military prison camps, some until well after the war ended.

Importantly, the decree fanned the flames of generalized anti-German intolerance as state-sanctioned volunteer “home guard” patriots stepped up campaigns to ban German language music and books. Vigilante mobs increasingly attacked and on occasion lynched German Americans and others suspected of “disloyalty.”

The Selective Service Act of May 18, 1917 required all males between the ages of 21 and 31 (later expanded to 18 and 45) to register with local draft boards. The law proved less popular than the actual decision to go to war and led to protests, some of which were attacked by soldier-led mobs, in cities around the country and in locations in the South and elsewhere, to armed defiance.

The draft also fueled anti-foreign resentment as it exempted aliens. The Act also propelled the rapid expansion of the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation (BI), charged with apprehending some three million men who never registered and another 338,000 “deserters” who failed to report.

The centerpiece of a broader set of repressive legislation, the Espionage Act of June 15, 1917 outlawed any attempts to obstruct the war effort, including opposition to conscription. Ostensibly designed to impede the operations of German agents, it primarily was used to silence antiwar opposition.

Of the more than 2,000 individuals charged by the DoJ and 1,055 convicted under the act, not one was prosecuted as a spy. (Still on the books, the Espionage Act has been used more recently in the prosecution of Chelsea Manning and other whistleblowers exposing U.S. war crimes and torture.) A section of the Act made it illegal to mail any materials “advocating or urging treason, insurrection, or forcible resistance to any law of the United States.” It gave the Post Office Department under the conservative Texas Democrat Albert Burleson broad discretionary powers to rule as “unmailable” any publication critical of the draft, the sale of war bonds and taxes, or which suggested the government was controlled by Wall Street or munitions manufacturers.

Its supplement, the Sedition Act of May, 1918 basically outlawed all criticism of the war and the government. It made the “uttering, printing, writing, or publishing any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language intended to cause contempt, scorn, contumely or disrepute” for the government, the Constitution, the flag, or the uniform of the Army or Navy punishable by up to 20 years in prison and a $20,000 fine. It banned “any language intended to incite resistance to the United States…” or that urged “any curtailment of production of any thing necessary to the prosecution of the war.”

It successfully mobilized war support, military enlistment and the sale of war bonds through patriotic spectacles and exhibitions while feeding carefully tailored war “news” to a compliant press. Its propagandists specifically tailored appeals to middle-class and working-class women, African Americans and the young as its volunteer educators and academics fashioned college and public school curriculum and texts.

It organized “Loyalty Leagues” to accelerate immigrant “Americanization” while a corps of its bilingual watchdogs, often university professors, monitored foreign language publications in search of Espionage and Sedition Act violations. The CPI also created and bankrolled the American Alliance for Labor and Democracy (AALD), headed by the American Federation of Labor (AFL) president Samuel Gompers, to keep organized labor “industrious, patriotic, and quiet” and combat the anti-war labor Left. (Kennedy, 72)

Significantly, the CPI promoted a climate of fear, suspicion and nationalist hysteria that resulted in countless incidents of intimidation and abuse of those suspected of disloyalty or insufficient war enthusiasm. It also urged the public to report anyone spreading defeatism and “cries for peace” to the Justice Department.

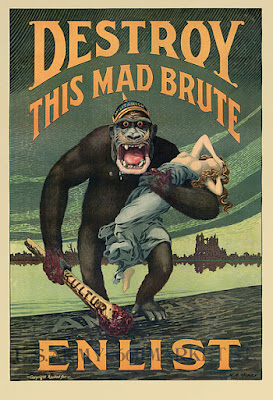

While promoting patriotic duty and self-sacrifice, its magazine articles, poster campaigns and millions of pamphlets demonized the enemy as an inhuman beast and barbaric “hun” and reproduced accounts of German atrocities, some of which were the work of British propagandists.

Established in 1908 as the DoJ’s investigative arm, a rapidly expanded BI not only pursued draft evaders and suspected enemy agents but became the prime wartime monitor of antiwar activity. With only two officers and clerks in April 1917, a relatively autonomous and largely clandestine MID would have, by November 1918, 1300 officers and civilian employees, a national network of undercover regional offices and field agents that coordinated the operations of unknown numbers of local police, private detectives, railroad employees, paid labor spies, traveling salespeople and numerous patriotic groups.

Joan Jensen, the historian of domestic military surveillance, noted the result:

“What began as a system to protect the government from enemy agents became a vast surveillance system to watch civilians who violated no law but objected to wartime policies or to the war itself. Agents considered such dissenters from government policy to be disloyal, pro-German, and generally malcontent. They became the enemy at home.” (Jensen, 160)

“Those surveillance bureaucracies rapidly developed a life of their own. In their world view the public was not to be trusted but in need of being controlled.” (Jensen, 166)

With 100,000 members in six hundred cities that June, APL would come to have some 250,000 volunteers in fourteen hundred localities by the end of the war. Provided by the DoJ with badges falsely identifying them as “Secret Service,” its operatives slandered and illegally detained citizens, opened mail and intercepted telegrams, infiltrated peace, civil liberties and labor organizations, burglarized offices and tapped phones, and forwarded upwards of three million reports of suspected disloyalty to their BI handlers.

Coordinated by DoJ agents and working alongside soldiers and sailors and local police, the APL also provided the ground troops for “slacker raids,” citywide dragnets and interrogations between April and September 1918 that detained thousands caught without draft cards.

In New York City alone on September 3-5, a task force of some 25,000 including 3,000 military personnel and thousands of APL members interrogated up to 500,000 men and detained 20,000 without draft classification cards in local jails and armories. Of the total, approximately one percent turned out to be “slackers.”

In 1919, the group’s chronicler proudly noted that what began as an effort to detect German agents had turned to rooting out “Bolsheviki, socialists, incendiaries, IWWs, Lutheran treason-talkers, Russel-lites [Jehovah’s Witnesses], Bergerites, all the other-ites, religious and social fanatics, third-sex agitators, long haired visionaries and work-haters from every race in the world.”

At the state level, by1918 local “councils of defense” were coordinating with the Army-funded Washington-based Council of National Defense and its 184,000 affiliates to enforce home front conformity. Local branches, with the assistance of women’s clubs and compiling records the whole time, canvassed door-to-door to boost food conservation, scrap drives and war bond subscriptions.

On occasion they paid intimidating night-time visits to the noncompliant, published “rolls of dishonor” of “bond shirkers” or splashed stigmatizing yellow paint on the nonconformist’s properties. Council members also assisted in the hunt for “slackers” and reported instances of “disloyal utterances” and alleged “pro-Kaiser” activity to the Feds.

Even before the BI and MID had fully mobilized, various state and local governments dominated by business and professional interests passed anti-syndicalist ordinances and utilized sheriffs’ departments, innumerable deputized volunteers, company cops and private detectives to deepen an all-out offensive, long underway, against the workers’ movement.

In practice, stepped-up federal action then gave increased license to extralegal abuses as radicals and strikers, branded as “pro-Kaiser” and increasingly after October 1917 as “Bolsheviki” (or both) were threatened, held incommunicado, forcibly run out of industrial districts, injured, tarred and feathered, murdered and lynched by boss-backed vigilantes.

In response to the mid-1917 strike wave, the Administration unleashed a two-pronged offensive. While extending offers of concessions, inclusion, mediation and initially ineffective efforts at regulation and price and profit controls to those AFL unions under Samuel Gompers’ leadership, it ratcheted up its offensive against the labor left.

Those AFL affiliates under Gompers’ sway largely agreed to what amounted to a “no strike pledge” in exchange for promises of improved conditions, wages and mediation contingent upon acceptance of the open shop. While that cooperation signaled a new “place at the table” for those participating unions, it also exposed the Left’s unyielding war opponents in the IWW and the SP to full-bore repression.

Following an “Emergency Convention” in St Louis the week war was declared, the SP issued a resolution voicing its “unalterable opposition” to it and called for “continuous, active and public opposition” to conscription, war appropriations and “vigorous resistance to all reactionary measures.” In response, party membership jumped by 12,000 in two months and votes for its candidates running on antiwar platforms in municipal and state elections spiked that November.

Suppression of the party escalated after those electoral gains as the BI and MID, aided by APL spies, ramped up surveillance and harassment. Its national leaders, among them Eugene Debs, were soon indicted and imprisoned under the Espionage Act. Its gatherings came under mob attack, the party’s Chicago headquarters was raided, and some 1500 of its 5000 party locals across the country were destroyed. The movement’s diverse press, essential to national organizing efforts and communications, was excluded from the mails.

With its revolutionary class perspectives, determination to build inclusive industrial unions across lines of race and nationality among the “unorganizable” and its tactical reliance on direct action, the IWW’s membership went from around forty to a hundred thousand between 1916 and late 1917. And as the overall number of war-boom strikes increased nationwide through mid-1917, the “Wobblies” stepped up their efforts long underway in precisely those sectors now deemed vital to the war effort — in Montana and Arizona copper, in Northwest timber, California and Upper Plains agriculture and elsewhere.

Wobbly activists had long preached the class struggle, anti-militarism and international solidarity but the organization had no official antiwar stance. With the passage of the Espionage Act, its National Executive actually counseled toning down any talk of sabotage and opposition to conscription. That cautious response did not protect it as their continuing struggles against the bosses were now branded as seditious attempts to impede the war effort.

Three days before war was declared, the Wobblie’s headquarters in Kansas City was destroyed by “off duty” Marines and militiamen. Similar assaults took place Duluth, Detroit and Seattle. The Chicago national office was broken into, its records stolen. Then, through that spring and summer, Wobblie organizers and rank-and-file “rough necks” across the West were subjected to a reign of terror executed by an array of commercial clubs, safety committees, and loyalty leagues.

Throughout the Northwest, Montana, and in Oklahoma following the “Green Corn Rebellion” offices and print shops were destroyed. Those arrested were denied the right of attorney or legal protection, were confined to “bull pen” stockades and subjected to vigilante violence. In the Fall 1917 about 125 Wobblies were jailed at Fresno, a third without charges, as branch secretaries at Los Angeles, San Pedro and Sacramento were indicted for conspiring to intimidate employers by threatening to strike for higher wages.

In late June, some 4700 largely immigrant, IWW-led, copper miners struck at Bisbee, Arizona. On July 12th over 2000 sheriff’s deputies armed and paid by the Phelps-Dodge mining company herded some 1200 suspected strikers, portrayed as “disloyal” and “pro-German,” onto cattle cars and “deported” them into the New Mexico desert. For months afterward, the copper bosses’ Citizen’s Protective League ruled the region and issued “passports” to enter the town and work. And that was before Federal troops, remaining in the region until well after the Armistice to protect production, had arrived.

In Butte, Montana on August 1st, vigilantes mutilated and lynched the Wobblie organizer and irrepressible antiwar voice Frank Little, who had come to assist a protracted struggle against Anaconda Copper.

In response to ongoing Wobblie-led militancy in the Pacific Northwest, the Army created the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumberman (“4L”), what amounted to a “yellow dog union” in some 500 lumber camps throughout the region. Built around a core of 30,000 soldiers and some 100,000 lumber workers who in order to work had to pledge support for the war and identify “Reds” to the MID, the 4L effectively barred recalcitrant radicals who, unemployed, then became subject to the draft under “work or fight” regulations. 4L members also assisted the MID with surveillance.

Then on September 5, 1917, nationally coordinated BI-led raids ransacked 48 IWW halls and additional homes in 33 cities. In an attempt to link the organization to the German War office, the Feds seized five tons of material from just the Chicago national office. The result was three mass trials at Chicago, Kansas City and Sacramento in which several hundred men were charged under the Espionage Act with hindering the war effort, inciting rebellion in the military, opposition to the draft and the bizarre charge that strike activities had infringed on the rights of employers.

In Chicago, following a four-month 1918 trial during which 101 defendants were portrayed in the press as anarchist bomb throwers, pro-German saboteurs and “Bolsheviki revolutionists,” they were found guilty after an hour deliberation. All were sentenced to up to 20 years with $2 million in fines.

All the while, nationwide defense committee efforts were virtually paralyzed by government harassment. Members of the Sacramento defense committee were themselves indicted. Twenty-seven of those arrested in Kansas and Oklahoma languished in a Wichita jail for two years while awaiting trial.

These raids, arrests, trials and costly defense efforts effectively crippled the organization during the most promising time in its history. The same held true for the SP. That lesson was not lost on the Justice Department. The use of indictments and trials became a regular weapon in the arsenal used to cripple radical organizations for decades to come.

Clearly the above brief sketch of what occurred in the early months after the United States entered the “Great War” suggests a great deal about the fragility of democratic rights and civil liberties during periods of national emergency. These developments were a prelude of things to come in the immediate postwar period, as the country continued to reel from the wars’ dislocations, unresolved contradictions and social tensions. That story will be taken up in a subsequent article.

Philip S. Foner, Labor and World War I 1914-1918, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 7 (1987).

John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925 (2002/1955) Chaps. 8-9.

Joan Jensen, Army Surveillance in America, 1775-1980, Part III: Legacy of World War I (1991).

Jeanette Keith, Rich Man’s War, Poor Man’s Fight: Race, Class, and Power in the Rural South During the First World War (2004).

David M. Kennedy, Over Here —The First World War and American Society (2004/1980).

David Montgomery, The Fall of the House of Labor. Chapter 6: “This Great Struggle for Democracy” (1987).

H. C. Peterson and Gilbert C. Fite, Opponents of War, 1917-1918 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1957).

William Preston, Jr., Aliens and Dissenters — Federal Suppression of Radicals, 1903-1933 (1995/1963).

Harry N. Scheiber, The Wilson Administration and Civil Liberties, 1917-1921 (1960).

William H. Thomas Jr., Unsafe for Democracy: World War I and the U.S. Justice Department’s Covert Campaign to Suppress Dissent (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008).

UNITED STATES ENTRY in World War I a hundred years ago set in motion a series of domestic transformations that continue to reverberate. In its efforts to mobilize society for “total war,” a still nascent corporate liberal state expanded its scope and authority and in doing so laid foundations and set precedents for the expansion of executive power and the rise of the national surveillance state.

That “war at home” was waged on numerous fronts as a federally coordinated ideological campaign shaped a hyper-nationalist climate of anti-foreign and anti-radical intolerance, coercion, extralegal violence and state repression that hammered all dissent. A brief survey of that early war period tells us much about how ugly, indeed dangerous, it can become for those deemed “disloyal,” “subversive,” “illegal” or “alien” in times of “national emergency” when conformity becomes a test of loyalty.

The “European War” had already been underway since August, 1914 when president Woodrow Wilson asked Congress for a formal declaration of war against Germany on April 2, 1917. (See: Ruff, on US Entry in World War I...) With that turn to war, the country’s ruling circles faced an immense set of challenges. They not only had to mobilize war production and allocate, raise and provision what became a four million-strong military force, but had to overcome widespread popular opposition and reluctance to join in the murderous, far-off bloodletting.

|

| "Come on in, America... The Blood is Fine!" |

Approximately twelve million newcomers had arrived during the latter 19th century, another eighteen million came prior to 1914 and those of German heritage made up the country’s largest single ethnic group. Millions of those “new immigrants” provided the labor at the base of the industrial economy but with the war, large numbers of them, hailing from the German and polyglot Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, the “Central Powers,” remained far from eager to take up arms against their homelands.

Additionally, with Tsarist Russia still part of the “Triple Entente” until after the 1917 "October Revolution," masses of Poles, Finns, Balts and Eastern European Jews also remained unsympathetic to the Allied cause. A sizable portion of the Irish American population, with the Dublin “Easter Rising” of 1916 and execution of its leaders fresh in its memory, also felt, at best, marked ambivalence regarding any support for the British. Besides, a great many of these pre-war numbers had immigrated not just for work and opportunity but to avoid military conscription.

Such were the social divides — not just of class, but race, ethnicity, gender and regional differences — that in his 1916 reelection campaign Wilson simultaneously campaigned on the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War” while promoting war “preparedness.”

A Southern-bred Democrat steeped in a white supremacist world view of American mission and racist notions of a civilizational hierarchy of peoples, he also played to deep-seated “old stock” anti-immigrant bigotry. Wilson repeated nativist calls for “100% Americanism” — the programmatic assimilation of “hyphenated-Americans,” those Southern and Eastern Europeans widely viewed as “inferior stock.” They were seen as the cause of the era’s social ills, labor strife and purveyors of “European radicalism.”

The war abroad intensified social tensions. Beginning in early 1915, some $2 billion in Entente orders for war-related commodities set off a boom, an expansion of investment, productive capacity and output and a related demand for labor. (The original triple Entente powers were France, the British Empire and the Russian Empire.)

That demand, already heightened by the war’s disruption of an annual cross-Atlantic flow of some 250,000 migrant workers, provided new leverage for the exclusivist skilled craft union affiliates of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), the railroad brotherhoods and the industrially organized United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), as well as those unorganized mobile workers able to sell their labor to the highest bidder.

It also presented new opportunities for the revolutionary unionists in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), veterans of more than a decade of struggles to organize the supposedly “unorganizable” among the largely immigrant “unskilled” of the industrial Northeast and Midwest and masses of itinerant workers engaged in timber, metal mining and agriculture across the Upper Plains and far West.

Northern labor demand also helped stimulate the first African-American “Great Migration” from the rural South, central to an understanding of the period. (See: Ruff, "A World Made More Unsafe: African Americans & World War I...")

Accelerating after U.S. entry, that war-induced boom not only brought immense corporate profits, but also fueled an inflationary spiral in the cost of living as prices for basic necessities outstripped wage increases. (Between 1913 and August, 1917 wholesale food prices rose 80% while the average retail price increased by 49%).

Living and working conditions declined as employers, encouraged by the initially relaxed enforcement of existing federal and state labor laws, eroded or ignored already minimal standards and protections. Varied and combined grievances — speedups, longer work weeks, deskilling of trades through mechanization, the introduction of “scientific management,” a lack of grievance procedures and union recognition, the “open shop” and increasingly perilous work conditions — provoked increases in union membership and a major upsurge in strike activity.

The period between April and early October 1917 witnessed some 3,000 documented walkouts by unionized and non-union workers in numerous industries, several of which involved upwards of 10,000 strikers and took on the character of city- or region-wide general strikes. That upsurge triggered a rapid response from a Washington establishment determined to prosecute the war, and by those corporate leaders eager to assure “industrial peace” and unprecedented profits.

With U.S. entry came a torrent of Executive Orders and Federal legislation that led, by early 1918, to the expansion or creation of some 5,000 wartime agencies, regulatory committees, oversight boards and federally-run corporations routinely headed by business elites dedicated to boosting and coordinating the war effort.

As a result, those elite “dollar-a-year men” succeeded in derailing those limited prewar Progressive Era regulatory initiatives curbing monopolies and the power of financial and industrial capital. As a result, the corporations dictated the terms of wartime mobilization as the war propelled the integration of the modern corporate liberal state.

Opening Rounds

Woodrow Wilson consistently set the national tone for what took place. In his December, 1915, Congressional call for military “preparedness,” he stated that the “gravest threats” to the nation were coming from foreign-born U.S. citizens busy spreading “the poison of disloyalty” and that “…such creatures of passion, disloyalty, and anarchy” should be “crushed out.”In his April, 1917 Congressional message, in which he defined the U.S. war aim as the liberal interventionist mission to make the world “safe for democracy,” he vowed that any “disloyalty” would meet with “a firm hand of stern repression.” That June, he charged that “German masters” were using socialists and the “leaders of labor” and “employing liberals in their enterprise” to “undermine the Government.”

The day war was declared and with anti-German hysteria already at a feverish pitch, Wilson resurrected the Alien Enemies Act, part of the “Alien and Sedition Acts” of 1798, to order the registration of all adult male German nationals. Broadened that fall, the measure barred all “enemy aliens” 14 years and older from places of “military importance” including Washington, D.C. and required them to seek permission to travel within the country or change residence.

The order was extended to include women the following April. Under its authority by war’s end, some 600,000 German citizens, regardless of their length of stay in the country or beliefs, would come to report to local post offices and police stations where they were fingerprinted, photographed, filled out forms and swore a loyalty oath. Denied due process and held under Justice Department administrative authority, some 6,300 of them were detained as a “deterrent” and 2,300 were confined to military prison camps, some until well after the war ended.

Importantly, the decree fanned the flames of generalized anti-German intolerance as state-sanctioned volunteer “home guard” patriots stepped up campaigns to ban German language music and books. Vigilante mobs increasingly attacked and on occasion lynched German Americans and others suspected of “disloyalty.”

The Selective Service Act of May 18, 1917 required all males between the ages of 21 and 31 (later expanded to 18 and 45) to register with local draft boards. The law proved less popular than the actual decision to go to war and led to protests, some of which were attacked by soldier-led mobs, in cities around the country and in locations in the South and elsewhere, to armed defiance.

The draft also fueled anti-foreign resentment as it exempted aliens. The Act also propelled the rapid expansion of the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation (BI), charged with apprehending some three million men who never registered and another 338,000 “deserters” who failed to report.

The centerpiece of a broader set of repressive legislation, the Espionage Act of June 15, 1917 outlawed any attempts to obstruct the war effort, including opposition to conscription. Ostensibly designed to impede the operations of German agents, it primarily was used to silence antiwar opposition.

Of the more than 2,000 individuals charged by the DoJ and 1,055 convicted under the act, not one was prosecuted as a spy. (Still on the books, the Espionage Act has been used more recently in the prosecution of Chelsea Manning and other whistleblowers exposing U.S. war crimes and torture.) A section of the Act made it illegal to mail any materials “advocating or urging treason, insurrection, or forcible resistance to any law of the United States.” It gave the Post Office Department under the conservative Texas Democrat Albert Burleson broad discretionary powers to rule as “unmailable” any publication critical of the draft, the sale of war bonds and taxes, or which suggested the government was controlled by Wall Street or munitions manufacturers.

Its supplement, the Sedition Act of May, 1918 basically outlawed all criticism of the war and the government. It made the “uttering, printing, writing, or publishing any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language intended to cause contempt, scorn, contumely or disrepute” for the government, the Constitution, the flag, or the uniform of the Army or Navy punishable by up to 20 years in prison and a $20,000 fine. It banned “any language intended to incite resistance to the United States…” or that urged “any curtailment of production of any thing necessary to the prosecution of the war.”

Hearts and Minds

On April 13, 1917 Wilson signed an executive order that created the Committee on Public Information (CPI) composed of the Secretaries of State, War and Navy and headed by a progressive Democrat, George Creel. The “Creel Committee” immediately launched an ideological offensive, a nationally coordinated propaganda campaign that assembled a sizable staff and some 75,000 volunteer writers, artists, advertisers, academics, entertainers and the early motion picture industry to shape public opinion. |

| CPI Liberty Bond poster, 1918 |

It organized “Loyalty Leagues” to accelerate immigrant “Americanization” while a corps of its bilingual watchdogs, often university professors, monitored foreign language publications in search of Espionage and Sedition Act violations. The CPI also created and bankrolled the American Alliance for Labor and Democracy (AALD), headed by the American Federation of Labor (AFL) president Samuel Gompers, to keep organized labor “industrious, patriotic, and quiet” and combat the anti-war labor Left. (Kennedy, 72)

Significantly, the CPI promoted a climate of fear, suspicion and nationalist hysteria that resulted in countless incidents of intimidation and abuse of those suspected of disloyalty or insufficient war enthusiasm. It also urged the public to report anyone spreading defeatism and “cries for peace” to the Justice Department.

While promoting patriotic duty and self-sacrifice, its magazine articles, poster campaigns and millions of pamphlets demonized the enemy as an inhuman beast and barbaric “hun” and reproduced accounts of German atrocities, some of which were the work of British propagandists.

|

| CPI posters demonized the enemy as an inhuman beast and barbaric “hun” |

Following Russia’s October Revolution, it rapidly labelled any stateside pro-Bolshevik activity as the work of “German agents.” Dovetailing with the period’s repressive measures and expanded policing powers, the CPI’s efforts were manifold as they dubbed all dissident opinion as “unpatriotic” and linked any antiwar or radical labor activity with “pro-Kaiserism.”

Homeland Security

The war measures provided new authority and expanded budgets to a number of federal agencies charged with policing the home front, central among them the Justice Department (DoJ) and its Bureau of Investigation (BI, forerunner of the FBI) and what became the Army’s Military Intelligence Division (MID).Established in 1908 as the DoJ’s investigative arm, a rapidly expanded BI not only pursued draft evaders and suspected enemy agents but became the prime wartime monitor of antiwar activity. With only two officers and clerks in April 1917, a relatively autonomous and largely clandestine MID would have, by November 1918, 1300 officers and civilian employees, a national network of undercover regional offices and field agents that coordinated the operations of unknown numbers of local police, private detectives, railroad employees, paid labor spies, traveling salespeople and numerous patriotic groups.

Joan Jensen, the historian of domestic military surveillance, noted the result:

“What began as a system to protect the government from enemy agents became a vast surveillance system to watch civilians who violated no law but objected to wartime policies or to the war itself. Agents considered such dissenters from government policy to be disloyal, pro-German, and generally malcontent. They became the enemy at home.” (Jensen, 160)

“Those surveillance bureaucracies rapidly developed a life of their own. In their world view the public was not to be trusted but in need of being controlled.” (Jensen, 166)

Volunteer Vigilantism

Thousands of local organizations assisted the BI and MID. The largest and most notorious of such “home guard” groups was the American Protective League (APL), initially formed and funded by Chicago business leaders in early 1917. Its agents operated as a surveillance arm for the BI and, secretly at the time, an adjunct of the MID.With 100,000 members in six hundred cities that June, APL would come to have some 250,000 volunteers in fourteen hundred localities by the end of the war. Provided by the DoJ with badges falsely identifying them as “Secret Service,” its operatives slandered and illegally detained citizens, opened mail and intercepted telegrams, infiltrated peace, civil liberties and labor organizations, burglarized offices and tapped phones, and forwarded upwards of three million reports of suspected disloyalty to their BI handlers.

Coordinated by DoJ agents and working alongside soldiers and sailors and local police, the APL also provided the ground troops for “slacker raids,” citywide dragnets and interrogations between April and September 1918 that detained thousands caught without draft cards.

In New York City alone on September 3-5, a task force of some 25,000 including 3,000 military personnel and thousands of APL members interrogated up to 500,000 men and detained 20,000 without draft classification cards in local jails and armories. Of the total, approximately one percent turned out to be “slackers.”

In 1919, the group’s chronicler proudly noted that what began as an effort to detect German agents had turned to rooting out “Bolsheviki, socialists, incendiaries, IWWs, Lutheran treason-talkers, Russel-lites [Jehovah’s Witnesses], Bergerites, all the other-ites, religious and social fanatics, third-sex agitators, long haired visionaries and work-haters from every race in the world.”

At the state level, by1918 local “councils of defense” were coordinating with the Army-funded Washington-based Council of National Defense and its 184,000 affiliates to enforce home front conformity. Local branches, with the assistance of women’s clubs and compiling records the whole time, canvassed door-to-door to boost food conservation, scrap drives and war bond subscriptions.

On occasion they paid intimidating night-time visits to the noncompliant, published “rolls of dishonor” of “bond shirkers” or splashed stigmatizing yellow paint on the nonconformist’s properties. Council members also assisted in the hunt for “slackers” and reported instances of “disloyal utterances” and alleged “pro-Kaiser” activity to the Feds.

The Left Under Attack

While the infant surveillance state network went after an array of religious and secular pacifists, its primary target was the organized Left — first and foremost the IWW, the resolutely antiwar Socialist Party, the agrarian radical Non Partisan League (NPL) on the Northern Plains and various anarchist circles. The war after all provided “a cloak of patriotism,” the “ideal camouflage” for those reactionary economic and political forces that had long sought federal assistance in their attempts to stamp out unionism and working-class radicalism, often viewed as synonymous. (Peterson & Fite, 72)Even before the BI and MID had fully mobilized, various state and local governments dominated by business and professional interests passed anti-syndicalist ordinances and utilized sheriffs’ departments, innumerable deputized volunteers, company cops and private detectives to deepen an all-out offensive, long underway, against the workers’ movement.

In practice, stepped-up federal action then gave increased license to extralegal abuses as radicals and strikers, branded as “pro-Kaiser” and increasingly after October 1917 as “Bolsheviki” (or both) were threatened, held incommunicado, forcibly run out of industrial districts, injured, tarred and feathered, murdered and lynched by boss-backed vigilantes.

|

| The IWW branded as “pro-Kaiser” |

Those AFL affiliates under Gompers’ sway largely agreed to what amounted to a “no strike pledge” in exchange for promises of improved conditions, wages and mediation contingent upon acceptance of the open shop. While that cooperation signaled a new “place at the table” for those participating unions, it also exposed the Left’s unyielding war opponents in the IWW and the SP to full-bore repression.

Following an “Emergency Convention” in St Louis the week war was declared, the SP issued a resolution voicing its “unalterable opposition” to it and called for “continuous, active and public opposition” to conscription, war appropriations and “vigorous resistance to all reactionary measures.” In response, party membership jumped by 12,000 in two months and votes for its candidates running on antiwar platforms in municipal and state elections spiked that November.

Suppression of the party escalated after those electoral gains as the BI and MID, aided by APL spies, ramped up surveillance and harassment. Its national leaders, among them Eugene Debs, were soon indicted and imprisoned under the Espionage Act. Its gatherings came under mob attack, the party’s Chicago headquarters was raided, and some 1500 of its 5000 party locals across the country were destroyed. The movement’s diverse press, essential to national organizing efforts and communications, was excluded from the mails.

With its revolutionary class perspectives, determination to build inclusive industrial unions across lines of race and nationality among the “unorganizable” and its tactical reliance on direct action, the IWW’s membership went from around forty to a hundred thousand between 1916 and late 1917. And as the overall number of war-boom strikes increased nationwide through mid-1917, the “Wobblies” stepped up their efforts long underway in precisely those sectors now deemed vital to the war effort — in Montana and Arizona copper, in Northwest timber, California and Upper Plains agriculture and elsewhere.

Wobbly activists had long preached the class struggle, anti-militarism and international solidarity but the organization had no official antiwar stance. With the passage of the Espionage Act, its National Executive actually counseled toning down any talk of sabotage and opposition to conscription. That cautious response did not protect it as their continuing struggles against the bosses were now branded as seditious attempts to impede the war effort.

Three days before war was declared, the Wobblie’s headquarters in Kansas City was destroyed by “off duty” Marines and militiamen. Similar assaults took place Duluth, Detroit and Seattle. The Chicago national office was broken into, its records stolen. Then, through that spring and summer, Wobblie organizers and rank-and-file “rough necks” across the West were subjected to a reign of terror executed by an array of commercial clubs, safety committees, and loyalty leagues.

Throughout the Northwest, Montana, and in Oklahoma following the “Green Corn Rebellion” offices and print shops were destroyed. Those arrested were denied the right of attorney or legal protection, were confined to “bull pen” stockades and subjected to vigilante violence. In the Fall 1917 about 125 Wobblies were jailed at Fresno, a third without charges, as branch secretaries at Los Angeles, San Pedro and Sacramento were indicted for conspiring to intimidate employers by threatening to strike for higher wages.

In late June, some 4700 largely immigrant, IWW-led, copper miners struck at Bisbee, Arizona. On July 12th over 2000 sheriff’s deputies armed and paid by the Phelps-Dodge mining company herded some 1200 suspected strikers, portrayed as “disloyal” and “pro-German,” onto cattle cars and “deported” them into the New Mexico desert. For months afterward, the copper bosses’ Citizen’s Protective League ruled the region and issued “passports” to enter the town and work. And that was before Federal troops, remaining in the region until well after the Armistice to protect production, had arrived.

|

| Bisbee, AZ, 1917: Armed sheriff's deputies load strikers on boxcars (Univ. of Arizona Special Colletions) |

In Butte, Montana on August 1st, vigilantes mutilated and lynched the Wobblie organizer and irrepressible antiwar voice Frank Little, who had come to assist a protracted struggle against Anaconda Copper.

In response to ongoing Wobblie-led militancy in the Pacific Northwest, the Army created the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumberman (“4L”), what amounted to a “yellow dog union” in some 500 lumber camps throughout the region. Built around a core of 30,000 soldiers and some 100,000 lumber workers who in order to work had to pledge support for the war and identify “Reds” to the MID, the 4L effectively barred recalcitrant radicals who, unemployed, then became subject to the draft under “work or fight” regulations. 4L members also assisted the MID with surveillance.

Then on September 5, 1917, nationally coordinated BI-led raids ransacked 48 IWW halls and additional homes in 33 cities. In an attempt to link the organization to the German War office, the Feds seized five tons of material from just the Chicago national office. The result was three mass trials at Chicago, Kansas City and Sacramento in which several hundred men were charged under the Espionage Act with hindering the war effort, inciting rebellion in the military, opposition to the draft and the bizarre charge that strike activities had infringed on the rights of employers.

In Chicago, following a four-month 1918 trial during which 101 defendants were portrayed in the press as anarchist bomb throwers, pro-German saboteurs and “Bolsheviki revolutionists,” they were found guilty after an hour deliberation. All were sentenced to up to 20 years with $2 million in fines.

All the while, nationwide defense committee efforts were virtually paralyzed by government harassment. Members of the Sacramento defense committee were themselves indicted. Twenty-seven of those arrested in Kansas and Oklahoma languished in a Wichita jail for two years while awaiting trial.

|

| IWW artist and political prisoner Ralph Chaplin's reminder... |

Clearly the above brief sketch of what occurred in the early months after the United States entered the “Great War” suggests a great deal about the fragility of democratic rights and civil liberties during periods of national emergency. These developments were a prelude of things to come in the immediate postwar period, as the country continued to reel from the wars’ dislocations, unresolved contradictions and social tensions. That story will be taken up in a subsequent article.

Suggested readings:

Melvyn Dubofsky, “We Shall Be All” — A History of the Industrial Workers of the World (1969), Part IV.Philip S. Foner, Labor and World War I 1914-1918, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 7 (1987).

John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925 (2002/1955) Chaps. 8-9.

Joan Jensen, Army Surveillance in America, 1775-1980, Part III: Legacy of World War I (1991).

Jeanette Keith, Rich Man’s War, Poor Man’s Fight: Race, Class, and Power in the Rural South During the First World War (2004).

David M. Kennedy, Over Here —The First World War and American Society (2004/1980).

David Montgomery, The Fall of the House of Labor. Chapter 6: “This Great Struggle for Democracy” (1987).

H. C. Peterson and Gilbert C. Fite, Opponents of War, 1917-1918 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1957).

William Preston, Jr., Aliens and Dissenters — Federal Suppression of Radicals, 1903-1933 (1995/1963).

Harry N. Scheiber, The Wilson Administration and Civil Liberties, 1917-1921 (1960).

William H. Thomas Jr., Unsafe for Democracy: World War I and the U.S. Justice Department’s Covert Campaign to Suppress Dissent (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008).